The third of my series of posts on poverty examines the transfer of poor laws from the British mainland to Ireland.

The Dublin House of Industry was established in 1772 to care for vagrants and beggars. In times of more general distress, the work of this and similar institutions in other cities was supplemented by ad hoc provision by the parishes raising funds by subscription. Reading accounts of the conditions that prevailed in the early 1780s, for example, it is clear that the response to widespread food and fuel shortages that occurred consisted of a combination of fire-fighting with limited financial resources and attempts by the government in Dublin to control markets and prices. Such attempts were actively opposed by merchants who often combined to frustrate philanthropic actions such as the donation of 2000 tons of free coal from the mine owner Sir James Lowther.

In addition to fund raising appeals by the parishes and government’s attempts to control markets and prices, some landlords offered alternative employment to workers displaced by such events as the failure of the flax crop in 1782 that had left weavers unable to ply their trade. In rural areas many communities took the law into their own hands, waylaying cartloads of grain destined for the cities.

According to James Kelly (Kelly, James. “Scarcity and Poor Relief in Eighteenth-Century Ireland: The Subsistence Crisis of 1782-4.” Irish Historical Studies, vol. 28, no. 109, 1992, pp. 38–62. www.jstor.org/stable/30008004.), “Acts of benevolence by landlords and clergy, and donations to institutions like the Houses of Industry, were vital for the control of distress in late eighteenth century Ireland. … In Dublin the House of Industry was the most important agent of relief, but it worked with local committees and was heavily reliant on donations…. while in the countryside landlords, wealthy farmers and clergy were indispensable.”

Note, however, that whereas there were numerous workhouses in England and Wales there were only a handful in Ireland, even though poverty and famines, or near famines, were much more common there. After the Act of Union at the commencement of the 19th century, the government in London considered various ways of tackling this problem which was beginning to effect social cohesion in England. A growing number of poor Irish families were migrating to England. Whilst they were not able to take advantage of the poor relief available there until they had established 5 years residence, their presence was perceived as a threat to both wages and social order.

(Astute readers will note a similarity between English attitudes to Irish immigrants 200 years ago and present day resentment towards migrants from Eastern Europe in England and from Mexico in the USA.)

Education

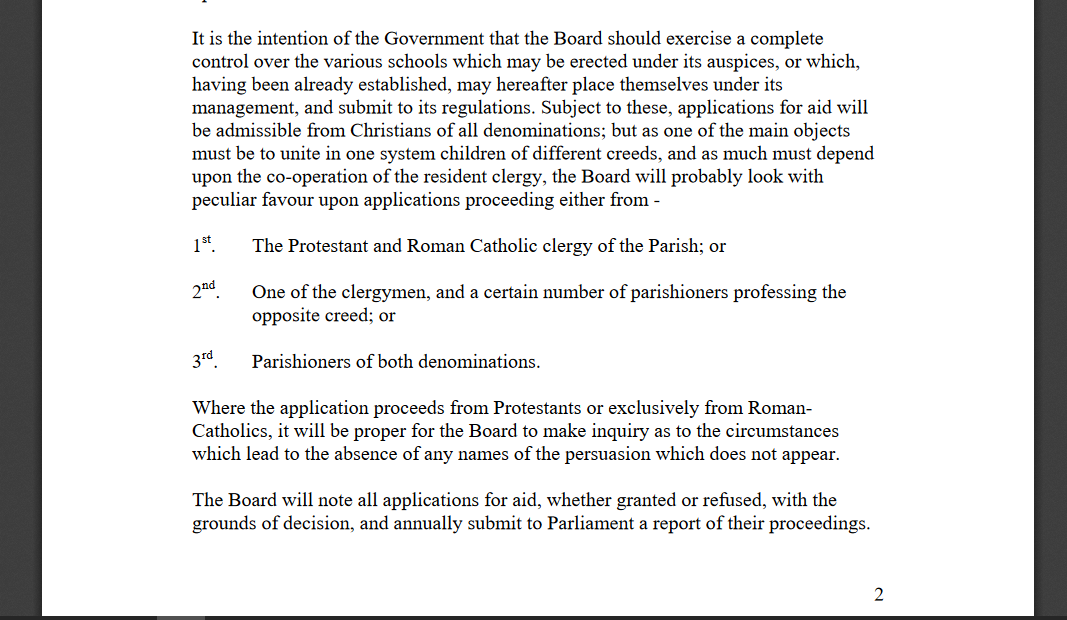

Education was seen as one important way of ending poverty, by equipping individuals with the skills to enable them to obtain work. During the second half of the 18th century a number of Protestant organisations established schools in Ireland. Catholics had been banned from providing education as part of the policy of suppressing the old religion. Once the ban was lifted, Catholic schools also began to appear. Unlike the Protestant schools, however, these did not receive government support. By the 1830s, the government decided to establish a National school system which would be multi-denominational, run by committees containing both Catholic and Protestant members.

Although this put Ireland ahead of the mainland in terms of state funded education, Ireland was not progressing economically or socially. A number of government initiated surveys and reports were commissioned but their recommendations were generally deemed to be too costly to implement. One such commission, headed by the Protestant Arch Bishop of Dublin, recommended that the poor law, as established in England, would not work in Ireland because of the lack of available work. This was unacceptable to the authorities in London who sent George Nicholls, one of the commissioners responsible for administering the poor law in England, to look at the situation in Ireland.

In an earlier post I described how the English regarded themselves as superior to the native populations of the lands they conquered. However well justified this attitude might have seemed given the evident successes achieved by English Soldiers, Seamen and Scientists, it looks today like extreme arrogance. The modern liberal view is that a person’s ethnic origin has no bearing on his or her intelligence or ability to acquire useful skills. This was not so in the first half of the nineteenth century. The English establishment viewed the native Irish in exactly the same way as they viewed the natives of Africa.

The remarks of the poor law commissioner, George Nicholls, illustrate this perfectly. “They seem to feel no pride, no emulation; to be heedless of the present, and reckless of the future. They do not … strive to improve their appearance or add to their comforts. Their cabins still continue slovenly, smoky, filthy, almost without furniture or any article of convenience or decency … If you point out these circumstances to the peasantry themselves, and endeavour to reason with and show them how easily they might improve their condition and increase their comforts, you are invariably met by excuses as to their poverty …’Sure how can we help it, we are so poor’ … whilst at the same time (he) is smoking tobacco, and had probably not denied himself the enjoyment of whiskey.”

(I have offered a possible explanation for the apparent indolence of Irish paupers based on recent studies in Neuroscience.)

His conclusion was that a new poor law should be enacted for Ireland which should include the provision of a network of 130 workhouses and that these institutions would not be permitted to provide relief other than within their walls. It was felt that this would deter all but those deemed to be the most deserving people from claiming relief. Each workhouse would have space for 800 persons, would be administered by a Board of Guardians and financed by a local property tax.

This policy was quickly implemented. When the potato crop failed in the second half of the 1840s this network of workhouses became the bases from which relief would be administered. They would prove to be utterly inadequate to perform the task, although, in fairness to the Boards of Guardians, the majority did their best with the limited resources available to them.

A very well written article that tries to be eminently fair in its treatment of both side, for there are two sides here. Ireland’s troubles, as in much of the British Empire, were caused by rank exploitation and abuse by absentee landlords and investors who cared not a whit about the people they either used as slave labor after dispossessing them, or tried to get rid of through forced emigration or by simply letting them die of famine. That too, is history, and much more widespread that just Ireland. All Western empires, to this very day, treated, and treat, their conquered and subdued “subjects” this way. Your history of Ireland is now the history of the Middle East.

LikeLiked by 1 person

“Education was seen as one important way of ending poverty, by equipping individuals with the skills to enable them to obtain work.”

~ This remains true today. But education should go much further by preparing our youth for adulthood: to make sound decisions, determine truth from fiction, and question policies that affect their lives.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you ladies (if that is not too offensive a term) for your kind comments. You are both right: exploitation continues today, at home and abroad. And educating young people to recognise the truth is more important than ever in these days of ‘fake news’ in which we are swamped with invented stories and alternative versions of the truth.

LikeLiked by 1 person

i dream of the day when Ireland will be united as one country again

LikeLiked by 1 person

Might be closer, thanks to Brexit. Although the political situation in NI at present looks a bit fraught!

LikeLike

Wouldn’t a united Ireland be an interesting side effect of Brexit!

LikeLike

It is entirely possible – though regrettable – that the ‘divorce’ of Britain from the EU could lead to the break up of the UK. A majority in Scotland voted to remain in the EU and some believe they can rejoin, post Brexit, if they first secure an exit from the UK.

LikeLike