I’ve been studying – and attempting to write a book about – the famine that devastated Ireland in the years 1845-52. No such study is complete without an analysis of the attitudes of the British towards Irish and English paupers. This is the first of a series of posts the overarching title of which is “Dealing with Poverty – a Historical Perspective”. This one deals with the evolution of the feeling of superiority that characterised the elites in Victorian Britain.

Exploration

By the nineteenth century British explorers and traders had for more than two hundred years traveled the world, discovering new lands bordering the Pacific and Indian Oceans. They developed trade links with the indigenous populations of these lands and profited enormously from that trade. They were not alone. Dutch, French, Spanish and Portugese merchants and adventurers were doing the same. Conflicts often ensued, engendering frequent wars. Britain usually came out on top and, by the beginning of the nineteenth century, large parts of Africa as well as the Indian sub-continent, all of Australia, New Zealand, Many Pacific Islands, Southern China and most of North America were governed by the British monarchy or its authorised agents.

The oldest of these colonies, those on the Eastern seaboard of North America, had formed themselves into the United States of America, fought for and won independence. But there were many other lands that offered opportunities for those seeking adventure.

Scientific advances

At the same time it could be said that Britain was leading the way in scientific

advancement. Some of those early explorers, such as James Cook, had pioneered techniques of surveying and map making as well as bringing back numerous geological and botanical specimens to add to the world’s fund of knowledge. Others had developed, and conducted experiments to prove, scientific theories that formed the basis of our modern understanding of chemistry, physics, astronomy and medicine.

Little wonder, then, that they regarded themselves, their beliefs and their systems of government to be superior to any others. In particular, the old ideas embodied by the Roman Catholic Church were deemed to be barely superior to the paganistic practices and idolatry of the natives of Africa, the far East and North America who had proved so easy to exploit. If certain among the Irish chose to cling to such outdated notions, if those same people were also poor and ignorant, then must there not be a causal link between the two? All that was necessary for the Irish to escape from their fate was for them to acquire the enlightened Protestant education that had produced the scholars, sailors and merchants that had made the acquisition of such an empire possible.

It was certainly the case that many of these colonies needed labour. They especially needed people who were capable of taking undeveloped land and turning it into productive farmland. Successful farmers from across the British Isles were, therefore, encouraged to emigrate to the colonies. And individuals who chose to defy the law by stealing could be sent as punishment to work as slave labour.

Philosophical and social studies

Educated Britons did not stop at developing and testing scientific theories. They concerned themselves with philosophical and social problems, especially those associated with the increasing population and the poverty that seemed inevitably to accompany it. How was it possible to ensure that the production of food kept pace with the growing number of mouths to feed? As the industrial revolution progressed and more people left the countryside for over-crowded cities, the old pattern of living, in which food was transported over relatively short distances to markets close to where people lived, was superceded by new modes of transport. Canals, railways and metaled roads made it possible to transport food from the fields to markets in the burgeoning centres of manufacturing.

A new field of study opened up as scholars attempted to understand the increasingly complex relationship between production and consumption and the problem of ensuring that workers, who no longer had access to the possibility of growing even some of their own food, were able to earn enough from their new activities, operating machinery, to provide the basic necessities of life.

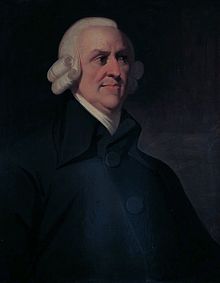

How to share the wealth produced by the activities of merchant explorers and, later, by machines, among the whole population, instead of enriching a few whilst the majority struggled in conditions of abject poverty? Men like Adam Smith pointed out that rent placed an added, unfair, burden on wealth creators. Others speculated about the relationship between increases in food production and the growth in population.

Population vs agricultural capacity

On the one hand the greater the number of people employed in all kinds of production, the more of everything that could be produced. On the other, the more food that was available, the longer people tended to live, especially young people. Whereas it was, in the past, not uncommon for children to die from any of a variety of diseases before reaching puberty, the more well fed they were the more likely they were to survive into adulthood and become parents themselves. Was there a limit on the ability of the available land to produce sufficient food?

One of the thinkers of the period, Thomas Malthus, examined the evidence and concluded that there was, indeed, a limit to the food production capacity of the land. The population had consistently grown at a faster rate than had the volume of food production. It was, he insisted, necessary to take steps to limit the growth of population, especially among the very poor. If they produced fewer children it would be easier to ensure that those children were well fed and housed to an acceptable standard. It might even be possible to end the practice of sending children out to work at a very young age. They could be sent, instead, to school where education would fit them for a better life.

Coming next: Evolution of Poor Laws and Their Application to Ireland.

Interesting history that’s still unfolding in our times.

LikeLiked by 1 person

To say this much in a short article: genius. Thanks for posting.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’d be very interested to read your book, Frank.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Stevie – I’d better get on with writing it then! I’m torn between a novel based around some of the events and a non-fiction account. Within the past few days I’ve been inspired by the story of one man in particular and I believe a novel based on his involvement in some of the most horrific aspects of the famine is where I’m headed. I must focus!

LikeLike